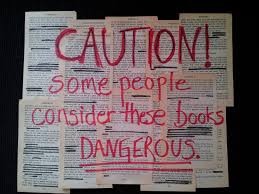

.Woohoooo! It’s Banned Books Week, a veritable high holiday for those of us who oppose the suppression of ideas, and believe in the value of the free flow of information.

As it happens, the stories of whistleblowers, visionaries, humanists, crazy people, and freethinkers throughout history who have expressed their opinions and ideas in the face of ridicule, punishment, threats of violence, and acts of violence, simply and regularly bring me to my knees.

(I’m sorry the other doctors abused you so righteously, Dr. Semmelweis. Thanks for the washing hands idea.)

As it happens, the stories of whistleblowers, visionaries, humanists, crazy people, and freethinkers throughout history who have expressed their opinions and ideas in the face of ridicule, punishment, threats of violence, and acts of violence, simply and regularly bring me to my knees.

(I’m sorry the other doctors abused you so righteously, Dr. Semmelweis. Thanks for the washing hands idea.)

(I’m sorry they burned your newspaper down Ida B. Wells. Thanks for refusing to shut up about the evil of lynching)

I free speech-ly admit that I am more or less obsessed with intellectual freedom. I read, dream and ruminate about the topic while burning oatmeal and braiding my daughter’s hair all wrong.

So obviously, I think Banned Books Week is a fabulous thing: An entire week set aside for the contemplation of the value of intellectual freedom, and the cost to a society when we smother dissent or silence voices that make us uncomfortable.

Only I’m uncomfortable.

Yesterday, the Guardian carried a story about Banned Books Week. In it, Jessica Herthel, co-author of I AM JAZZ, a picture book about a child who feels that he was born a girl in a boy’s body, had this to say. “I urge everyone to celebrate Banned Books Week by picking up a book that some closed-minded person out there wanted desperately to keep out of your hands.”

No, I’m not uncomfortable with the subject matter of I AM JAZZ. What do you take me for? Boo, I say. Boo on efforts to ban I AM JAZZ or any other book for that matter. Yay for acceptance of and respect for all people whatever their gender identification.

What I’m uncomfortable with is the notion implied by Herschel’s quote that the best way to celebrate Banned Books Week is to read the books that “closeminded” wannabe book banners “out there” don’t want us to read.

If there is a downside to the otherwise glorious event called Banned Books Week, perhaps it has to do with locating the threat to our intellectual freedom in the U.S. at this time, as lying firmly outside of ourselves.

Yes, I support reading “banned” or “targeted for banning” books as an act of solidarity with their authors, and with the people who identify with a book’s characters or value a book’s perspective. I’m not sure, however, that choosing our Banned Book Week reads from a list of books banned by otherpeople is the most intellectually brave thing to do.

The impulse to ban books arises from a cognitive habit that is near universal of humans: The initial resistance to truly open-minded consideration of belief systems, ideas, theories and conceptions that by their very existence challenge the “obvious” “rightness” and “truth” of our own current views. Many of us are at some times in our lives are made uncomfortable or feel downright threatened by alternative belief systems, ideas, theories and conceptions, and most everyone experiences attachment to favored ones.

So are we really challenging our OWN intellectual limitations and prejudices by reading books that other people “want desperately to keep out of our hands”?

I can’t help but feel that when we get right down to it, wannabe book banners are basically the Amish of thought police, sallying forth to try to control the transmission of ideas in their not-very-speedy horse and buggies (apologies to the Amish).

So obviously, I think Banned Books Week is a fabulous thing: An entire week set aside for the contemplation of the value of intellectual freedom, and the cost to a society when we smother dissent or silence voices that make us uncomfortable.

Only I’m uncomfortable.

Yesterday, the Guardian carried a story about Banned Books Week. In it, Jessica Herthel, co-author of I AM JAZZ, a picture book about a child who feels that he was born a girl in a boy’s body, had this to say. “I urge everyone to celebrate Banned Books Week by picking up a book that some closed-minded person out there wanted desperately to keep out of your hands.”

No, I’m not uncomfortable with the subject matter of I AM JAZZ. What do you take me for? Boo, I say. Boo on efforts to ban I AM JAZZ or any other book for that matter. Yay for acceptance of and respect for all people whatever their gender identification.

What I’m uncomfortable with is the notion implied by Herschel’s quote that the best way to celebrate Banned Books Week is to read the books that “closeminded” wannabe book banners “out there” don’t want us to read.

If there is a downside to the otherwise glorious event called Banned Books Week, perhaps it has to do with locating the threat to our intellectual freedom in the U.S. at this time, as lying firmly outside of ourselves.

Yes, I support reading “banned” or “targeted for banning” books as an act of solidarity with their authors, and with the people who identify with a book’s characters or value a book’s perspective. I’m not sure, however, that choosing our Banned Book Week reads from a list of books banned by otherpeople is the most intellectually brave thing to do.

The impulse to ban books arises from a cognitive habit that is near universal of humans: The initial resistance to truly open-minded consideration of belief systems, ideas, theories and conceptions that by their very existence challenge the “obvious” “rightness” and “truth” of our own current views. Many of us are at some times in our lives are made uncomfortable or feel downright threatened by alternative belief systems, ideas, theories and conceptions, and most everyone experiences attachment to favored ones.

So are we really challenging our OWN intellectual limitations and prejudices by reading books that other people “want desperately to keep out of our hands”?

I can’t help but feel that when we get right down to it, wannabe book banners are basically the Amish of thought police, sallying forth to try to control the transmission of ideas in their not-very-speedy horse and buggies (apologies to the Amish).

The people who send letters to libraries, or circulate petitions asking that Huckleberry Finn, Diary of a Part-Time Indian, or I Am Jazz to be taken off of shelves, or not read out loud, seem almost quaint in their methods, and thankfully, the books they try to run down tend (though not always!) to get more well-known, and garner more champions, and more readers, as a result of the targeting.

For instance, as the Guardian story related, though a contingent of parents successfully got a school to cave on doing an out-loud reading of “I Am Jazz”, a quickly-organized alternative read-aloud at a public library in the same town drew an immense supportive crowd.

It could be argued that as a means of challenging one’s intellectual integrity, reading books that someone ELSE wants banned — but that one is entirely comfortable reading— is pretty much the equivalent of shooting hogtied manatees in a fruit-cup-size Tupperware container.

So then what might those of us who want more of an intellectual challenge during Banned Books Week do?

How about we seek out books “banned” only by our own internal “censor”. The one who rolls her eyes, or causes us to experience skyrocketing blood pressure when passing books in libraries or bookstores that espouse “that absurd perspective”, or “that dangerous view”, or by the author we’ve “heard” is a moron?

How about reading a book that challenges a deeply held belief or conception about what we ourselves believe to be incontrovertibly “true” or “false”? Or one that contains the kind of perspectives on political, scientific, spiritual, or philosophical issues that makes our stomachs clench just considering them?

Isn’t that ultimately the point of not wanting books banned? In order to provide ourselves as thinkers with a rich diversity of human perspectives on issues, puzzles, and mysteries? I didn’t always think so.

My first notion about the meaning and purpose of intellectual freedom was based on a more or less complete misunderstanding of the philosopher Voltaire’s thoughts on the matter. I read a one-sentence summary of them (first mistake!) by one of his biographers (Evelyn Beatrice Hall) which is often misattributed to Voltaire as a quote.

It goes:

”I disapprove of what you say, but will defend to the death your right to say it.”

I took the statement to mean that it was necessary to defend the right of idiots to express stupid, detestable, invalid, or “wrong” thoughts and opinions only in order to guarantee that smart, admirable, valid and “right” thoughts and opinions could and would be protected. Protecting all speech, was the price a society had to pay to create protection for valuable speech. I heartily agreed!

It never occurred to me — ace defender of the right of others to hold stupid, detestable, invalid or “wrong” ideas and opinions — to ask a very important question of my most magnanimous self: What if an idea that I thought inconceivable, ridiculous, or otherwise invalid turned out to contain value or truth? How likely was it that in any moment I was likely to be “right” and able to discern validity and truth in all matters? How would I know if one of my own opinions, conceptions, or beliefs was in some way partly inaccurate or flat out wrong?

As history shows us again and again if we’ll only look, and my older ever so slightly wiser self has come to realize, consensus is no guarantee of ethical or even scientific validity. Dissent is a precious resource. Personal humility about the possible limitations or “wrongness” of what we currently believe to be true and incontrovertible is another.

I now champion the protection of “all” speech (obvious “fire” shouting scenarios aside) rather than “tolerate” it. Not as the cost of doing intellectual business, but as a defense against my own limitations as a “knower” and “believer” of things. I now defend the right of all to express opinions and thoughts — even the ones that strike me initially as stupid, detestable, invalid or “wrong”, in order to preserve the maximum sized resource pool in which insight, clarity, or wisdom might lurk.

The Buddhists keep imaginary birds perched on their shoulders to remind them of the transitory nature of life and the imminence of death. I now try to keep one on my own shoulder to remind me to engage with intellectual humility in the realm of knowledge. For the record, she’s a chicken and her name is Sophie, and when I forget to pay attention to her, I tend to end up with bird poop on my clothes. She usually wears a t-shirt that says: “Epoche, this”. It's in the wash at the moment.

For instance, as the Guardian story related, though a contingent of parents successfully got a school to cave on doing an out-loud reading of “I Am Jazz”, a quickly-organized alternative read-aloud at a public library in the same town drew an immense supportive crowd.

It could be argued that as a means of challenging one’s intellectual integrity, reading books that someone ELSE wants banned — but that one is entirely comfortable reading— is pretty much the equivalent of shooting hogtied manatees in a fruit-cup-size Tupperware container.

So then what might those of us who want more of an intellectual challenge during Banned Books Week do?

How about we seek out books “banned” only by our own internal “censor”. The one who rolls her eyes, or causes us to experience skyrocketing blood pressure when passing books in libraries or bookstores that espouse “that absurd perspective”, or “that dangerous view”, or by the author we’ve “heard” is a moron?

How about reading a book that challenges a deeply held belief or conception about what we ourselves believe to be incontrovertibly “true” or “false”? Or one that contains the kind of perspectives on political, scientific, spiritual, or philosophical issues that makes our stomachs clench just considering them?

Isn’t that ultimately the point of not wanting books banned? In order to provide ourselves as thinkers with a rich diversity of human perspectives on issues, puzzles, and mysteries? I didn’t always think so.

My first notion about the meaning and purpose of intellectual freedom was based on a more or less complete misunderstanding of the philosopher Voltaire’s thoughts on the matter. I read a one-sentence summary of them (first mistake!) by one of his biographers (Evelyn Beatrice Hall) which is often misattributed to Voltaire as a quote.

It goes:

”I disapprove of what you say, but will defend to the death your right to say it.”

I took the statement to mean that it was necessary to defend the right of idiots to express stupid, detestable, invalid, or “wrong” thoughts and opinions only in order to guarantee that smart, admirable, valid and “right” thoughts and opinions could and would be protected. Protecting all speech, was the price a society had to pay to create protection for valuable speech. I heartily agreed!

It never occurred to me — ace defender of the right of others to hold stupid, detestable, invalid or “wrong” ideas and opinions — to ask a very important question of my most magnanimous self: What if an idea that I thought inconceivable, ridiculous, or otherwise invalid turned out to contain value or truth? How likely was it that in any moment I was likely to be “right” and able to discern validity and truth in all matters? How would I know if one of my own opinions, conceptions, or beliefs was in some way partly inaccurate or flat out wrong?

As history shows us again and again if we’ll only look, and my older ever so slightly wiser self has come to realize, consensus is no guarantee of ethical or even scientific validity. Dissent is a precious resource. Personal humility about the possible limitations or “wrongness” of what we currently believe to be true and incontrovertible is another.

I now champion the protection of “all” speech (obvious “fire” shouting scenarios aside) rather than “tolerate” it. Not as the cost of doing intellectual business, but as a defense against my own limitations as a “knower” and “believer” of things. I now defend the right of all to express opinions and thoughts — even the ones that strike me initially as stupid, detestable, invalid or “wrong”, in order to preserve the maximum sized resource pool in which insight, clarity, or wisdom might lurk.

The Buddhists keep imaginary birds perched on their shoulders to remind them of the transitory nature of life and the imminence of death. I now try to keep one on my own shoulder to remind me to engage with intellectual humility in the realm of knowledge. For the record, she’s a chicken and her name is Sophie, and when I forget to pay attention to her, I tend to end up with bird poop on my clothes. She usually wears a t-shirt that says: “Epoche, this”. It's in the wash at the moment.

As I said, I’m extremely glad Banned Books Week exists. It’s a wonderful opportunity to support those books and voices that are in danger of being silenced. It reminds us that attempts to curtail the free flow of ideas still exist in the U.S. and agreement on the “good” of unchecked intellectual freedom is by no means universal. Wannabe book banners should be opposed, and good on all of us who do oppose book banning.

But I hope those of us who care about intellectual freedom will not begin and end our experience with Banned Books Week by patting ourselves on the back (however softly) for our virtue as individuals who would never attempt to ban a book like those “close-minded people”.

We could take the opportunity of Banned Books Week to put some of our own intellectual rigidities and unexamined certitudes to the test. We could identify one controversial perspective that we find ridiculous, potentially destructive, or otherwise devoid of value, and seek out a book by an author who believes the perspective has value. A book that those who hold the perspective hold in high esteem. No cheating by reading the least accomplished, most terribly presented version of the perspective.

We could each pick up a book that we probably wouldn’t notice if anyone banned.

But I hope those of us who care about intellectual freedom will not begin and end our experience with Banned Books Week by patting ourselves on the back (however softly) for our virtue as individuals who would never attempt to ban a book like those “close-minded people”.

We could take the opportunity of Banned Books Week to put some of our own intellectual rigidities and unexamined certitudes to the test. We could identify one controversial perspective that we find ridiculous, potentially destructive, or otherwise devoid of value, and seek out a book by an author who believes the perspective has value. A book that those who hold the perspective hold in high esteem. No cheating by reading the least accomplished, most terribly presented version of the perspective.

We could each pick up a book that we probably wouldn’t notice if anyone banned.